Introduction: The Microcosmos in the Compost Bin

Within a fermenting mixture of vegetable waste and cow manure, a magnificent drama invisible to the naked eye is unfolding. Trillions of microorganisms—bacteria and fungi—act like a well-trained symphony orchestra, taking the stage in precise sequence to transform complex organic matter into stable humus. Recently, scientists have, for the first time, detailed the complete succession map of microbial communities during the composting of tomato stalks and cow manure using high-throughput sequencing technology. This is not merely a “cast list” of microbes but a crucial code for understanding the composting process and optimizing fermentation techniques.

First Movement: Spring Overture—Microbial Pioneers of the Mesophilic Phase

In the first few days of composting, the temperature gradually rises from ambient to above 50°C. This stage is like the beginning of spring, with everything coming back to life.

Early Bacterial Prosperity

At this time, bacteria of the Firmicutes phylum become active first. This phylum includes the familiar genus Bacillus, experts at decomposing cellulose and hemicellulose. Like the first flowers of spring, they utilize the most readily available simple sugars and starches, rapidly multiply, release heat, and drive the pile temperature upward.

Fungi’s Preliminary Appearance

Among fungi, various Ascomycota begin to appear. Genera like Aspergillus and Acremonium are relatively active. These fungi can secrete various enzymes and start degrading complex components in plant cell walls.

The microbial community at this stage is relatively diverse, with various microbial groups “blooming like a hundred flowers,” reserving sufficient biomass and enzyme systems for subsequent high-temperature fermentation.

Second Movement: Summer Climax—Thermophilic Specialists of the Thermophilic Phase

When the pile temperature exceeds 55°C and remains high, composting enters its most intense “summer.” Most mesophilic microorganisms cannot tolerate such high temperatures, while a special group of “thermophilic specialists” usher in their golden age.

Bacterial Heat-Resistant Shift

The abundance of Chloroflexi increases significantly during this period, peaking around day 25. This phylum includes many thermophilic or heat-tolerant species capable of continuing to decompose organic matter at high temperatures. Simultaneously, some thermophilic Firmicutes and Actinobacteria remain active.

Fungal Thermophilic Stars

The shift in the fungal community is even more pronounced. Thermomyces becomes the star of this stage. This fungus has an optimal growth temperature between 45-55°C and is a typical thermophilic decomposer. It is particularly adept at degrading hemicellulose and some cellulose, serving as one of the main forces for lignocellulose degradation during the high-temperature phase.

This stage is also critical for compost sanitization. High temperatures not only accelerate organic matter decomposition but also effectively kill pathogens and weed seeds. Thermophilic microorganisms act like professional “sanitizers” and “decomposers,” completing crucial transformations in harsh conditions.

Third Movement: Autumn Transition—Transitional Groups of the Cooling Phase

As easily degradable organic matter is largely consumed, heat production decreases, and the pile temperature begins to drop from its peak (40-50°C). This marks the entry into composting “autumn,” with another significant microbial community shift.

Bacterial Community Adjustment

The abundance of Chloroflexi begins to decline, while the relative abundance of Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria increases. Proteobacteria includes many bacteria with diverse metabolic capabilities, likely involved in nitrogen transformation and decomposition of remaining organic matter. Actinobacteria are known for producing geosmin (earthy odor) and decomposing stubborn organic matter.

New Fungal Protagonists

Among fungi, Mycothermus replaces Thermomyces as the dominant fungus. This fungus may specialize in decomposing the remaining, more difficult-to-degrade macromolecules from the previous two stages, such as some lignin and complex aromatic compounds.

Microorganisms at this stage act like a “fine-processing team,” handling the “tough bones” left from earlier stages and further converting intermediate products into more stable forms.

Fourth Movement: Winter Stability—Synthesis Masters of the Maturation Phase

When the pile temperature drops close to ambient, composting enters the final maturation and stabilization phase, equivalent to “winter” in the microbial world.

Bacterial Community Stabilization

Microbial community diversity decreases, but the structure tends to stabilize. Some bacteria capable of synthesizing humus begin to play important roles. Although the total bacterial count decreases, the remaining populations are elites that have survived “natural selection,” particularly adapted to the mature environment.

Continued Fungal Action

Ascomycota continues to maintain dominance, while the abundance of Basidiomycota may increase. Basidiomycota are among the fungi with the strongest lignin degradation capabilities in nature, possibly responsible for final lignin transformation during the maturation phase.

Microorganisms at this stage act like “architects,” synthesizing complex humic macromolecules from simple organic molecules. Humus is the ultimate product of composting, capable of improving soil structure and enhancing water and nutrient retention.

The “Conductors” of Microbial Succession: Temperature and Oxygen

What conducts this four-season symphony of microbes? The study points to two key “conductors”: temperature and oxygen.

Temperature is the most direct selective pressure. Different microorganisms have different optimal temperature ranges. As pile temperature naturally changes, the microbial community automatically shifts, much like different seasons have different dominant plants.

Oxygen influences metabolic pathways. During days 20-25 of composting, oxygen consumption is highest, and local anaerobic zones may appear within the pile. This may lead to a brief proliferation of some facultative anaerobic or microaerophilic microorganisms and may also promote the production of certain anaerobic metabolites like methyl sulfide.

Turning operations affect both factors simultaneously: they introduce fresh oxygen, regulate pile temperature, and physically mix materials and microbes. Therefore, turning frequency and timing directly influence the succession path of microbial communities.

The Hidden Connection Between Microbes and Odor

This study also revealed specific links between microorganisms and compost odor:

- Ammonia-Producing Related Bacteria:Identified 13 bacterial genera significantly associated with ammonia production, such as Desulfitibacter, Paenibacillus, etc.; and 4 related fungal genera, such as Meyerozyma, Alternaria, etc.

- Sulfur-Containing Compounds:The production of malodorous sulfur-containing substances like methyl sulfide is related to the formation of anaerobic zones within the pile, and the existence of these zones is closely linked to turning frequency and microbial respiration.

- Aromatic Compounds:The large number of aromatic hydrocarbons detected may be related to precursor substances in cow manure and the transformation capabilities of specific microorganisms.

These findings provide clear targets for reducing compost odor through microbial regulation. For example, efficient ammonia-oxidizing bacteria can be inoculated to reduce ammonia release, or turning strategies can be optimized to reduce anaerobic microenvironments.

Practical Application: Compost Management Based on Microbial Knowledge

Understanding microbial succession patterns allows for more scientific management of the composting process:

- Stage-Specific Inoculation:Inoculate corresponding functional microorganisms at different composting stages, e.g., cellulose-degrading bacteria in the initial stage, thermophilic lignin-degrading fungi in the high-temperature phase.

- Precise Turning:Determine turning timing based on microbial activity intensity and oxygen demand, rather than fixed time intervals.

- Process Parameter Optimization:Adjust carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, moisture, and aeration to create optimal environmental conditions for target microbial growth.

- Odor Control:Intervene specifically against microorganisms or metabolic pathways that produce malodorous substances.

Conclusion: Harnessing Microbial Intelligence for Sustainable Production

The orchestrated succession of microbes in composting reveals nature’s blueprint for transforming waste into a stable resource. This knowledge elevates composting from an art to a precise science, enabling us to “conduct” microbial communities for faster, cleaner, and more efficient organic recycling. This microbial toolbox is fundamental to circular agriculture and soil regeneration.

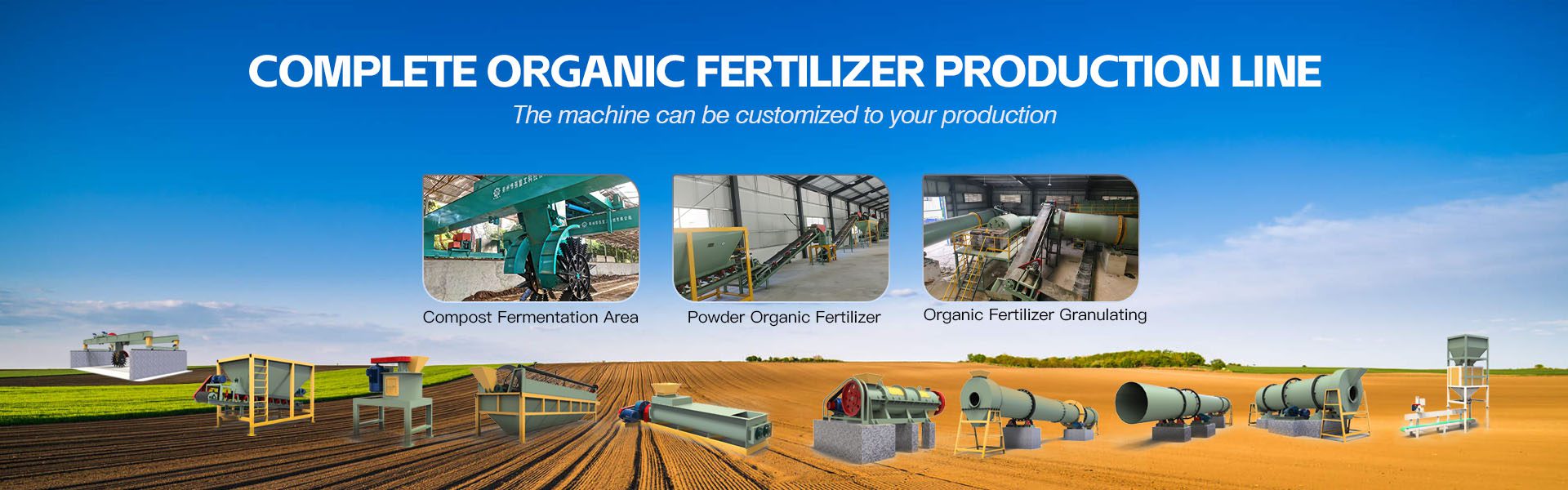

This biological process is the vital first stage in a complete organic fertilizer production line. The mature compost produced, often using a windrow composting machine, serves as the foundational organic base. It can be processed into commercial products through a bio organic fertilizer production line. For integrated nutrient solutions, this compost can be blended with mineral nutrients in an npk fertilizer production line. Here, an npk blending machine ensures precise formulation, and granulation equipment like a disc granulator (in a disc granulation production line) or a double roller press granulator shapes the final product, completing the npk fertilizer production process from biological decomposition to formulated nutrient delivery.

Thus, by synergizing natural microbial wisdom with advanced manufacturing technology, we create a powerful system for sustainable agriculture, turning organic waste into precision-engineered soil health solutions.